Are you fascinated by sculptures? Do you enjoy exploring the rich history and stories behind these incredible works of art? If so, you’re in for a treat! In this article, we’ll take a journey through time and space as we explore 33 of the most awe-inspiring sculptures in the world.

From ancient masterpieces to modern marvels, these sculptures will capture your imagination and leave you in awe.

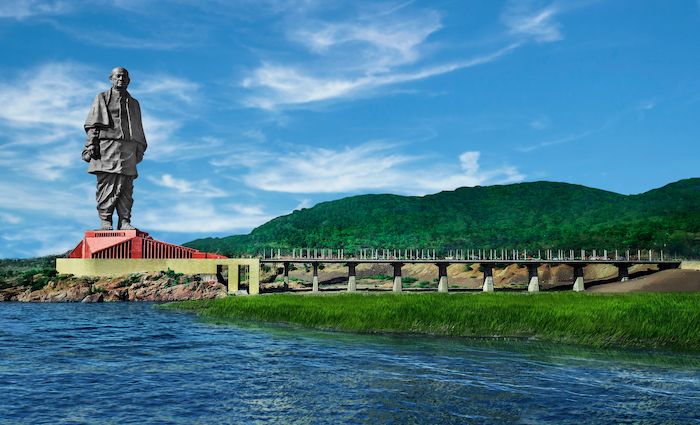

33. Statue of Unity

Ram V. Sutar | 2013-2018 AD | Bronze, Reinforced Concrete | Kevadia, Gujarat, India

We’re starting with a colossal statue and recent addition in the realm of global landmarks. The Statue of Unity located in the Indian state of Gujarat depicts Vallabhbhai Patel. Patel emerged as one of modern India’s independence leaders. Moreover, historian Kishore Makwana tells us that Patel became the country’s first deputy prime minister.

This massive monument to Patel and modern India is in his home state of Gujarat. Designed by Ram V. Sutar, Makwana tells us that the Statue of Unity is touted as the tallest in the world. However, scholars Alexander E. Davis and Ruth Gamble say it is not without political and environmental controversy.

It rises 597 feet over the controversial Sardar Sarovar Dam. Inaugurated by Indian Prime Minister, Narendra Modi in October 2018, Davis and Gamble say the statue cost over $400 million to construct. Thus, to some observers, this is a modern marvel. On the other hand, for other observers, it is an expensive political project. However, time will tell as many monuments have faced similar criticism

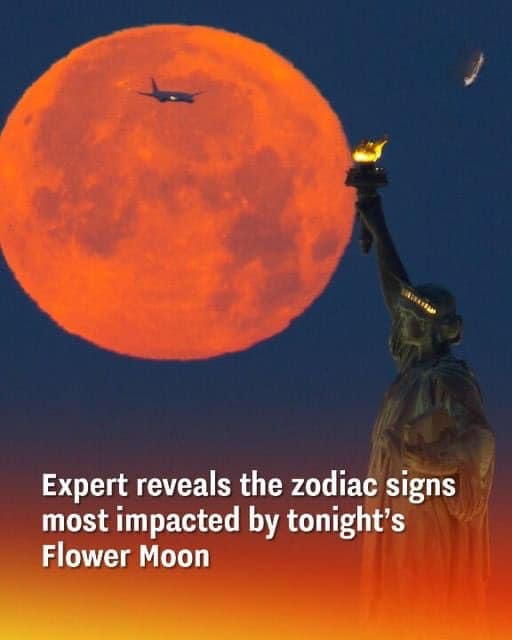

32. Statue of Liberty

Frédéric Auguste Bartholdi | 1886 AD | Copper | New York City

One monument the Statue of Unity had to surpass to get the title of world’s tallest is this all-American symbol in New York City. Indeed, few images define America to most more than New York’s Statue of Liberty.

Now, the Statue of Liberty may seem as all-American as apple pie and the 4 th of July, but not so. In fact, as historian Yasmina Sabina Khan explains, the monument originated in France. Khan says that French legal scholar Édouard-René Lefebvre de Laboulaye came up with the idea for the monument. Saddened by Abraham Lincoln’s assassination in April 1865, and eager to promote close ties between the US and France, he set out to raise funds for the monument.

To Laboulaye and the French, the statue came to be called La Liberté Éclairant le Monde or Liberty Enlightening the World. The Statue of Liberty’s journey from abstract conception to colossal monument involved highs and lows for its major organizers. Khan mentions that prominent organizers included sculptors Frédéric Auguste Bartholdi and Gustave Eiffel (of Eiffel Tower fame).

Although it took two decades to realize, the Statue of Liberty rapidly emerged as a powerful symbol of American democratic ideals and aspirations. For example, historian Edward Berenson explains has been a rallying symbol across many decades, but particularly in the aftermath of 9/11.

Not ready to book a tour yet? Check out our guide to all things New York City for more info.

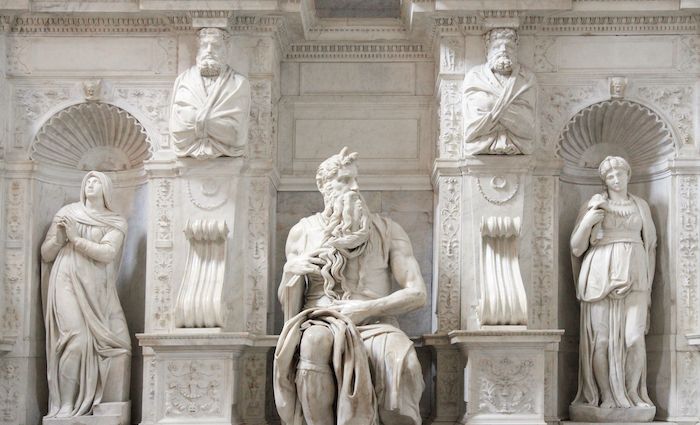

31. Moses

Michelangelo | c. 1513-1515 AD | Marble | Church of San Pietro in Vincoli, Rome

Michelangelo probably would say this piece involved one of if not his most demanding client. But when that client offers you powerful sponsorship and happens to be a pope in 16 th century Rome, you must put up with it.

Michelangelo’s Moses emerged as part of the tomb designed by the artist for Pope Julius II (Giuliano della Rovere; elected 1503-1513). Art historian H.W. Janson describes the sculpture’s expression as both “watchful and meditative.”

One fact gives an indication of how demanding this project was for Michelangelo. For instance, art historian Nigel McGilchrist points out that the tomb for Pope Julius II spanned over 40 years of Michelangelo’s career (1505-1545). Furthermore, McGilchrist continues, project details changed constantly.

In fact, after so many decades, Moses is the only piece surviving from the original proposal to be in place at the tomb. As art historian Alta Macadam explains, Moses is the reason tourists gather at this church.

30. The Boxer at Rest

Unknown | Late 4 th-2nd Century BC | Bronze | The National Roman Museum-Palazzo Massimo alle Terme, Rome

Also known as the Terme Boxer after the museum where it is displayed. It is a remarkable example of Hellenistic art from Ancient Greece. As scholar Nigel McGilchrist explains, boxing was a huge deal in the ancient world. For instance, Ancient Greeks valued boxing as a form of military training.

The bronze is striking for its realism. This is one tough guy. For example, you can see the wounds to the boxer’s head post-boxing match. Moreover, art historian Ian Chilvers points out that even the now missing eyes would have been very realistic.

According to scholar Alta Macadam, people in late antiquity intentionally buried this piece, probably to save it from invaders. As a result, this bronze is a rare example of a piece made by the indirect lost-wax method. Art historian Ian Chilvers says this means that individual pieces were made separately and then melded together.

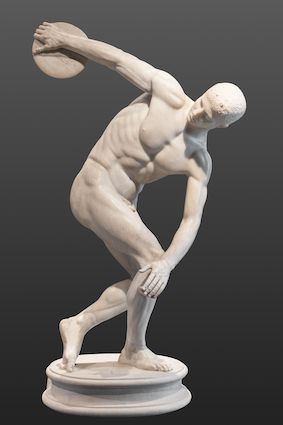

29. Discobulus (Discus Thrower)

Myron (Original) | c. 450 BC (Original) | Marble (Copies) | Multiple Locations (Copies)

Arguably one of the most recognizable poses to be immortalized in art. This work of noted mid-5 th century BC Greek sculptor Myron only survives in multiple Ancient Roman copies. For example, art historian Ian Chilvers says the best copy (from the 2 nd century AD) is at the National Roman Museum Palazzo Massimo alle Terme in Rome. Furthermore, another copy is displayed in the British Museum, London.

Unfortunately, art historian Ian Chilvers says no visual record survives of Myron’s most famous work. It depicted a bronze Cow and once stood in the Ancient Agora in Athens. Moreover, Chilvers says that ancient commentators were awed by its naturalism.

28. Venice’s Bronze Horses

Unknown | 4 th Century BC (Originals) | Bronze | St. Mark’s Basilica, Venice

With apologies to Seabiscuit and other legendary horses, few of our equine friends are as famous as this group. Moreover, few horses or works of art have been celebrated trophies for as many conquerors as Venice’s Bronze Horses. In fact, as historian RJB Bosworth notes, the list is long-from Crusaders to Napoleon’s army.

These horses likely date to 4 th century BC Greece. Nero then brought them to Rome. However, Emperor Constantine took the horses to his new capital (Constantinople). So, how did they get to Venice?

This is where the Crusaders come into the story. During the Crusader sacking of Constantinople in 1204, the bronzes were removed to Venice. In Venice, they stood guard over the balcony of St. Mark’s Basilica where the doge would make public appearances. Next, historian Andrew Roberts says Napoleon seized the bronzes and displayed them in Paris. After Napoleon’s fall, the horses found their way back to Venice.

Currently, copies adorn St. Mark’s Basilica in Venice. The originals are displayed inside.

Not ready to book a tour? Check out our guide to Venice for more info.

27. Bird in Space

Constantin Brancusi | 1923 AD | Marble (Original); Bronze Copies | Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York (Original)

An incredibly abstract piece from one of the world’s most accomplished sculptors. Bird in Space by Franco-Romanian sculptor Constantin Brancusi according to art historian Elizabeth Munro captures the essence of a bird taking off upward into the air.

Bird in Space even caused a famous art scandal in the 1920s. In 1926, American customs officials wanted to tax Bird in Space as a raw metal rather than consider it art which would have been duty-free. Eager to display Bird in Space at an exhibition in New York, Brancusi paid customs duties.

However, as art historian Ian Chilvers points out, Brancusi successfully sued the Customs Office in 1928. There’s a joke about bureaucratic red tape somewhere.

Furthermore, Chilvers says that by his death in 1957, Brancusi was widely regarded as the greatest sculptor of the 20th century. Moreover, the Philadelphia Museum of Art boasts an impressive collection of Brancusi’s works.

26.The Motherland Calls

Yevgeny Vuchetich & Nikolai Nikitin | 1967 AD | Reinforced Concrete | Volgograd, Russia

A colossal monument dedicated to a massive historical event. That event would be the Second World War’s Battle of Stalingrad (July 17, 1942-February 2, 1943). Moreover, historian Antony Beevor tells us that it was here that Nazi Germany’s war effort received a fatal setback at the hands of Soviet defenders. Although WWII raged for more than 2 years from that point, German forces never recovered from defeat at Stalingrad.

Today’s Russian city of Volgograd is the city formerly known as Stalingrad. Furthermore, the monument rises 172 feet in the air. However, when measuring the tip of the sword, it extends to 280 feet. As a result, historian Susanne Schattenberg tells us at its October 1967 inauguration, Soviet officials hailed the Motherland Calls as the world’s tallest statue. Sadly, at present scholars say the monument needs urgent repairs and renovation.

25. The Little Dancer of Fourteen Years

Edgar Degas | c. 1880-1881 AD | Wax Original, Bronze Copies | National Gallery of Art, Washington D.C.

You probably associate the name Edgar Degas with Impressionist painting. However, Degas also produced wax sculptures in his career. In fact, art historian Ian Chilvers says Degas took up this medium as his eyesight failed. Only one of these waxes, however, was exhibited in his lifetime.

That piece was the Little Dancer of Fourteen Years , exhibited at the fifth Impressionist exhibition in 1881. The original wax sculpture comes complete with an actual tutu.

Furthermore, New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art holds one bronze copy. Another copy is displayed at the Tate Modern, London.

24. Equestrian Statue of Marcus Aurelius

Unknown | c. 176-180 AD | Bronze | Capitoline Museums, Rome

A good example of imperial Roman statuary. Roman Emperor (and Stoic philosopher) Marcus Aurelius (r. 161-180 AD) appears confident and in control. Why would he appear otherwise? As historian Christopher Kelly explains, Marcus Aurelius ruled a still dominant empire and won victories over Germanic tribes.

This piece is lucky to still exist for multiple reasons. One reason is that early Christians destroyed many examples of Roman imperial equestrian statuary. In fact, scholar John A. Pinto says this Marcus Aurelius statue survived precisely because it was mistaken for a depiction of Emperor Constantine.

The second obstacle this Marcus Aurelius statue survived involved modern political troubles. For example, architectural historians Raffaele Panella and Maria Luisa Tugnoli explain that the monument sustained damage from an anti-government bomb attack in 1979. As a result, the statue had to be restored until moved inside the Capitoline Museums in 1991.

Fortunately, today you can see the original inside Rome’s Capitoline Museums and a copy in the adjacent Piazza del Campidoglio.

23. The Burghers of Calais

Auguste Rodin | 1884-1889 AD | Bronze | Calais, France (Original); Multiple Locations

Art historian H.W. Janson once said French sculptor Auguste Rodin was the “first sculptor of genius since Bernini.” Of course, great sculptors like Antonio Canova would take offense to Janson’s opinion. Janson at least was right to point out Rodin’s talent.

The French city of Calais’s municipal council likely had no idea their project to commemorate a local hero would result in such a famous work of sculpture. Art historian Elizabeth Munro says the event Rodin depicts relates to the Hundred Years’ War between France and England. Specifically, it shows seven of the city’s leading citizens offering their lives in return for sparing the rest of Calais.

Moreover, Rodin’s The Burghers of Calais emerged as a popular symbol of republican ideals in turn of the century France. For example, art historian Richard Swedberg believes Rodin’s piece reflects an appeal to the collective civic courage of ordinary citizens. In other words, Swedberg believes this piece inspires democratic civic responsibility in action.

Today, as art historian Ian Chilvers says, you can see The Burghers of Calais around the world. Copies abound from Paris, London, New York, Philadelphia, and Tokyo among others.

22. Christ the Redeemer

Paul Landowski, Heitor da Silva Costa & Georghe Leonida | 1922-1931 AD | Concrete, Soapstone | Rio de Janeiro

Towering 125 feet high on Rio’s Corcovado Mountain, this Art Deco monument wows visitors from around the world. The statue of Christ the Redeemer is the product of French sculptor Paul Landowski and Brazilian engineer Heitor da Silva Costa. Moreover, Romanian sculptor Georghe Leonida contributed facial features. Scholar Ashim Paun says that while plans had been in the works for a religious monument since 1859, momentum only picked up in 1922, the centennial of Brazilian independence from Portugal.

According to scholar Mark Holston, Christ the Redeemer became an instant symbol of Rio and one of the most iconic landmarks in the Americas from its dedication in October 1931. However, Holston says it almost did not feature the iconic Christ with outstretched arms.

In fact, locals ridiculed Landowski’s original design. Scholar Bruno Carvalho explains that it initially called for a figure of Christ holding a globe. Moreover, Holston says that design earned the nickname “ Cristo da Bola ” (Christ with a Ball). However, whether holding a ball or with outstretched arms, this monument would always register as the key image of Brazil.

21. Mount Rushmore National Memorial

Gutzon Borglum | 1927-1941 AD | Granite | Keystone, South Dakota

Unlike most entries discussed here, Mount Rushmore’s famous sculptures exist because of a desire to promote tourism. Specifically, as scholar Eric Dregni explains, the site was meant to attract tourists to South Dakota in the 1920s. The brainchild of a local historian, few initially bought his idea to generate tourist interest and money for this corner of the state.

However, with the idea couched in patriotic terms, momentum picked up over the 1920s. Eventually, Dregni explains, Congress got involved and offered to fund. Moreover, art historian Ian Chilvers tells us sculptor Gutzon Borglum dramatically fashioned the faces of American presidents Washington, Jefferson, Lincoln, and Theodore Roosevelt.

His vision was to memorialize the great men who oversaw some of the most important events in history and had the vision to push America to something great. Gutzon’s son Lincoln Borglum completed the finishing touches on the memorial in 1941. The memorial though has its share of controversies.

In fact, there is a counter monument nearby. The Crazy Horse Memorial is located less than 20 miles away from Mount Rushmore. Original sculptor Korczak Ziolkowski worked with Gutzon Borglum on Mount Rushmore. Scholar Eric Dregni tells us that Ziolkowski received an invitation from Lakota Chief Henry Standing Bear to build a memorial for Native Americans.

Work thus began on the Crazy Horse Memorial in 1948 and it is still ongoing. Unlike Mount Rushmore, the Crazy Horse Memorial is privately directed and (by choice) does not have Congressional funding.

20. Mannekin Pis

Jérôme Duquesnoy the Elder | c.1619 AD (Original Copy) | Bronze | Brussels

You’ll be hard-pressed to find a more beloved and humorous example of sculpture. Yet, Brussels can claim both Mannekin Pis and the more modern Jeanneke Pis. For its part, Mannekin Pis (Dutch for “little pissing man”) has a colorful story.

Scholar Catherine Emerson says this tiny bronze plays an outsized role in the Belgian capital’s history. For instance, Emerson tells us Mannekin Pis has been coopted for different purposes in both festive and contentious times. In recent decades, Mannekin Pis dresses for special occasions.

In fact, you just may see Mannekin Pis dressed in a Belgian national team soccer jersey or wearing a surgical mask. Today’s bronze dates from 1965. You can see the original at the Brussels City Museum.

19. Artemision Bronze- Zeus or Poseidon

Unknown | c. 460 BC | Bronze | National Archaeological Museum, Athens

Zeus or Poseidon? Is he holding a thunderbolt or a trident? If you couldn’t already tell, there is a lot archaeologists don’t know about this masterpiece of ancient Greek statuary.

According to archaeologist Roza Proskynitopoulou, it dates from roughly 460 BC. One thing we do know is that it was discovered at sea off the coast of Cape Artemision on the island of Evia, Greece.

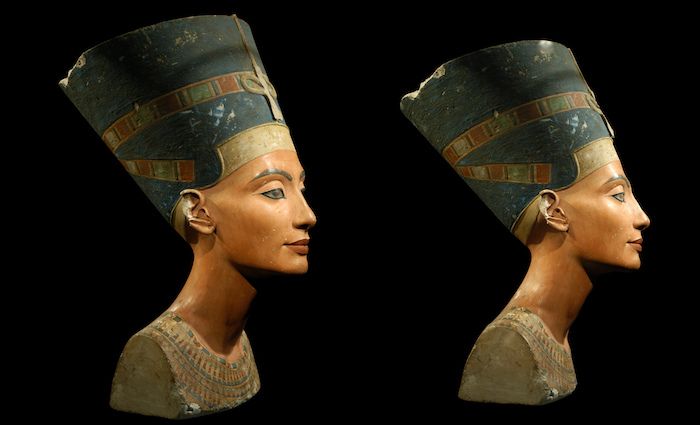

18. Bust of Nefertiti

Unknown | c. 1351-1334 BC | Limestone, Painted Stucco | The Egyptian Museum of Berlin, Berlin State Museums, Berlin

While not as famous as Cleopatra in the popular imagination about Ancient Egypt, Nefertiti (meaning “the beautiful one has come”) is certainly a significant figure. For example, Egyptologist Joyce Tyldesley reminds us that Nefertiti was a popular queen as wife to pharaoh Akhenaten. Furthermore, she became the mother-in-law to a guy you’re familiar with: Tutankhamun (King Tut).

Scholars believe the bust of Nefertiti is the most significant piece of Ancient Egyptian art housed in Continental Europe. Moreover, art historian Elizabeth Munro notes unlike earlier representations of generic deities, Nefertiti boasts clearly visible and beautiful human qualities.

Indeed, Nefertiti’s bust boasts a history worthy of such a significant object. Discovered by a German archaeologist at Tell el-Amarna, Egypt in 1912, the piece was quickly spirited out of the country. Following its installation at Berlin’s Neues Museum in 1913, scholar Kurt G. Siehr says the piece became so popular that many Germans considered it a national treasure.

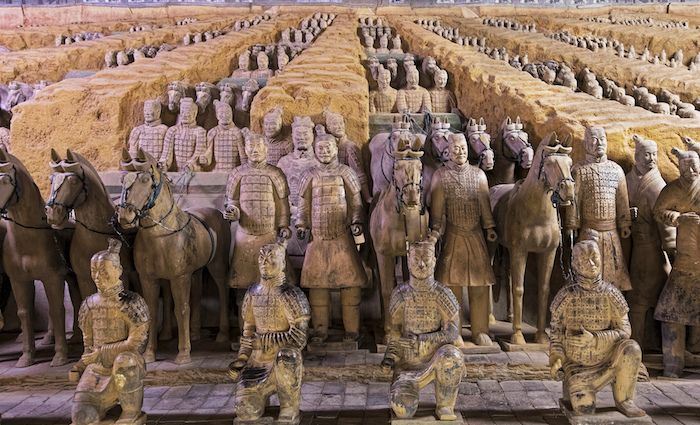

17. Mausoleum of the First Qin Emperor (Terracotta Army)

Unknown | 246-210 BC | Terracotta | Xi’an, China

By his death in 210 BC, Qin Shi Huangdi unified China and became its first emperor. As you might imagine, such an important ruler naturally planned an eternal resting place worthy of his accomplishment. The result was this mausoleum which 2 nd century BC Chinese historian Sima Qian claimed represents the universe in miniature.

That universe required a massive army to follow the emperor. For instance, art historian Jane Portal tells us that there are more than 8,000 soldiers (and horses) within the so-called Terracotta Army. It is not just the number of terracotta warriors that is impressive. Moreover, Portal reminds us that each warrior has unique facial features. Thus, the sculptures give a realistic impression of individuality. That is quite the eternal entourage.

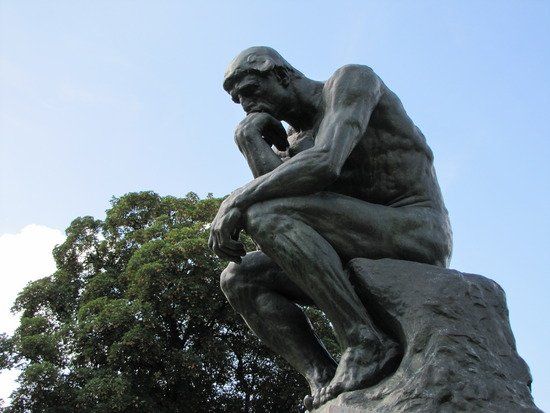

16. The Thinker

Auguste Rodin | 1904 AD Original | Bronze | Rodin Museum, Paris; Multiple Locations

What’s this guy thinking about? Quite a lot in fact if you consider his original purpose. Conceived in about 1880, Rodin intended this piece to crown a monumental work inspired by Dante’s “Inferno” called the Gates of Hell. Although as art historian H.W. Janson points out the Gates of Hell never materialized, the project produced several iconic sculptures like The Kiss.

The most famous of these, however, is Rodin’s The Thinker. According to art historian Ian Chilvers, it was cast in bronze in 1904 by Fonderie Alexis Rudier. Although we know it by that name, its original title was The Poet. Continuing with the Dante theme, The Poet (or Thinker) was supposed to be contemplating the nature of the scenes played out in the Gates of Hell.

Today scholars hail The Thinker as a testament to the creative power of our minds. As such, you’ll find bronze copies across the globe.

15. Apollo Belvedere

Unknown | c. 130 AD | Marble | Vatican Museums, Vatican City

You must use your imagination, but here Apollo, Greek god of the sun is practicing one of his patron arts: archery. In fact, Apollo draws an arrow readying to load it in his also lost bow. Apollo Belvedere is likely more than 2,000 years old. However, as art historian Ian Chilvers explains, it is likely based on an earlier Classical or Hellenistic Greek bronze. Its name derives from the papal Belvedere Palace (part of the Vatican Museums), where it has been displayed since 1511.

However, as part of the Treaty of Tolentino (1797), Napoleon forced the Pope to ship hundreds of works of art to Paris. Moreover, historian RJB Bosworth tells us Napoleon specifically included Apollo Belvedere by name in his wish list of Papal-owned art. It stayed in Paris between 1798 and 1815.

Furthermore, Apollo Belvedere is a good example of how tastes change in art. For instance, art historian Ian Chilvers says Apollo Belvedere long held the distinction of being a supreme masterpiece of the art world. Moreover, it inspired artists like Bernini and Sir Joshua Reynolds. However, Chilvers says that since the late 19th century, its reputation declined among art critics. Despite the cool critical reception, Apollo Belvedere still draws crowds at the Vatican Museums.

Not ready to book a tour? Check out our Vatican Guide for more info.

14. Perseus with the Head of Medusa

Antonio Canova | c.1790-1801 AD (Original) | Marble | Vatican Museums, Vatican City

A.K.A. Perseus Triumphant. In other words, legendary Italian sculptor Antonio Canova is depicting a victorious Perseus, the legendary founder of Mycenae and of the Perseid dynasty. Moreover, as art historian Christopher M.S. Johns explains, Perseus represented Canova’s triumph as the greatest sculptor since antiquity. Why?

Because as Johns explains, Pope Pius VII in 1801 placed Perseus with the Head of Medusa on the same pedestal once occupied by the legendary Apollo Belvedere. By this act, Pius VII literally put Canova’s work on the most exalted of pedestals in the art world.

Indeed, Canova by this point had powerful admirers like Napoleon. In fact, historian Andrew Roberts tells us Napoleon offered Canova the special protection of the French army during his invasion of Italy in 1796. Napoleon eventually went further in his offers to Canova. Roberts says Napoleon was such a huge fan that he wanted Canova to permanently move to Paris at state expense.

Although Canova declined Napoleon’s offer, he also turned down similar proposals to live in Vienna and St. Petersburg. Indeed, by the early 19 th century, Canova secured fame with works like his 1793 Psyche Revived by Cupid’s Kiss. This piece is currently included in the Louvre’s collection in Paris. A marble copy of Perseus produced in 1804-1806 is currently on display at New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art.

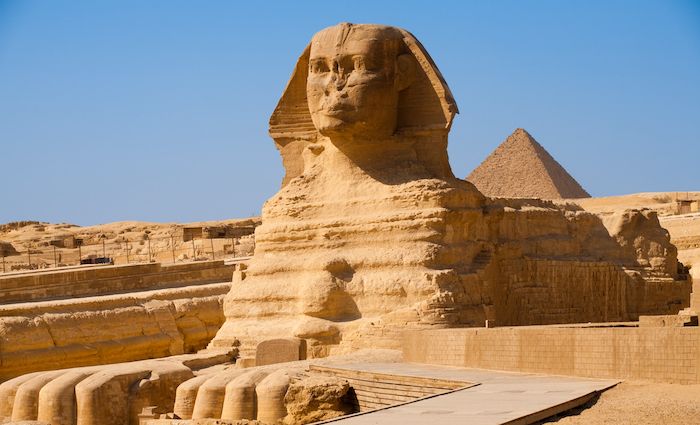

13. Great Sphinx at Giza

Unknown | c. 2520 BC | Limestone | Giza, Egypt

Few entries here are as mysterious as the Great Sphinx. For starters, nobody knows exactly how old it is. However, scholar Richard Cavendish gives us a good example by pointing out an ancient restoration project. Cavendish explains that Pharoah Thutmose IV restored the Great Sphinx around 1400 BC!

Moreover, scholar Christiane Zivie-Coche says in Greco-Roman times the Great Sphinx still was carefully preserved. In later centuries, Egypt’s Arab conquerors called the Great Sphinx Abu ul-Hol (Father of Terror). Richard Cavendish notes that one Egyptian ruler in 1380 damaged the Great Sphinx. Furthermore, soldiers at times used the Great Sphinx for target practice.

As with many things involving the Great Sphinx, Cavendish says we do not know if it is missing its nose because of erosion or vandalism. However, such mysteries only fuel more interest.

12. Apollo and Daphne

Gian Lorenzo Bernini | 1622-1625 AD | Marble | Galleria Borghese, Rome

When you see Bernini’s Apollo and Daphne for yourself, you might think it is meant to be displayed in this particular hall of Rome’s Galleria Borghese. And you would be correct. For example, art historian Franco Marmondo explains that Bernini sculpted this work specifically for the room. And more importantly, Apollo and Daphne became the biggest sensation in the art world.

Bernini’s complex piece captures the moment when Apollo reaches for his love (the nymph Daphne), only to find that Daphne’s father had her turn into a laurel tree. Moreover, art historian Alta Macadam says that Bernini modeled Apollo on the famous Apollo Belvedere .

Art historian Loyd Grossman says Apollo and Daphne was one of three major works Bernini executed for Cardinal Scipione Borghese between 1621 and 1625. The other sculptures are Bernini’s David, and the Rape of Prosperina. However, as his contemporary biographer Baldinucci suggested, Apollo and Daphne caused “all Rome” to rush out and see Bernini’s “miracle.” Baldinucci could make any publicist today fear for their job.

Not ready to book a tour? Check out our Vatican Guide for more info.

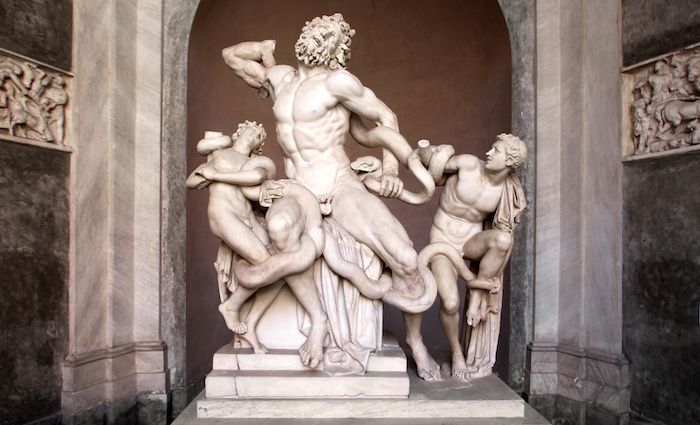

11. Laocoön and Sons

Attributed to Agesander, Polydorus, & Athenodorus of Rhodes | c. 1 st Century BC | Marble | Vatican Museums, Vatican City

Here we see a man and his sons being crushed to death by two sea serpents as divine punishment by Apollo. Their deaths mark the dramatic climax of the legendary Trojan Wars. That is because the man depicted is the Trojan high priest Laocoön.

Laocoön tried to warn Troy of “Greeks bearing gifts” like the Trojan Horse filled with invading soldiers. You can see his realization that the warnings fall on deaf ears through the pain etched in his face.

Roman writer Pliny the Elder attributes the sculpture to Rhodian sculptors. Moreover, art historian Ian Chilvers says it’s clear that Laocoön was considered one of the most famous sculptures in antiquity. However, this famous piece was buried and lost to the world for centuries.

Its discovery in Rome in 1506 AD revolutionized the art world. For instance, art historian Ian Chilvers says Michelangelo drew deep inspiration from studying Laocoön .

10. Pauline Bonaparte as Venus Victrix (“Venus Victorious”)

Antonio Canova | 1805-1808 AD | Marble | Galleria Borghese, Rome

The younger sister of Napoleon, Pauline Bonaparte shared some characteristics with the ancient goddess of beauty, love, and lust, Venus (Aphrodite to the Greeks). For starters, contemporaries considered her one of the most beautiful women in Europe. Like Venus, Pauline knew how to stir drama. For example, historian Andrew Roberts says she often annoyed her brother Napoleon with her love affairs and lavish lifestyle.

In fact, as biographer Frank McLynn explains, Napoleon was furious to learn Pauline commissioned this piece from sculptor Antonio Canova. Although Napoleon loved Canova’s work, he took issue with his sister’s willingness to spend that kind of cash (and pose semi-nude).

Canova’s sculpture is very much at home in Rome’s Galleria Borghese. That is because Pauline’s second husband was none other than Camillo Borghese, 6 th Prince of Sulmona. In other words, you could say Pauline kind of owned the place.

9. Ecstasy of St. Teresa

Gian Lorenzo Bernini | 1647-1652 AD | White Marble | Cornaro Chapel, Church of Santa Maria della Vittoria, Rome

Bernini and many later art historians believe this to be his finest work. Bernini depicts Teresa of Ávila, a Spanish noblewoman turned nun who was canonized by Pope Gregory XV in 1622.

Art historian Jonathan Unglaub explains that the Ecstasy of St. Teresa is the product of a time where Bernini worked largely for private patrons. Hence, here Bernini worked on the Cornaro Chapel within the Church of Santa Maria della Vittoria.

Moreover, as art historian Elizabeth Munro explains, Bernini’s Ecstasy of St. Teresa is a creative extravaganza. One element that distinguishes this piece is that it is not just a work of sculpture. In fact, as art historian Ian Chilvers points out, Bernini incorporated sculpture, architecture, and painting to create a deeply pious and moving experience.

8. Unique Forms of Continuity in Space

Umberto Boccioni | 1913 AD | Plaster (Original); Bronze Copies | Museum of Contemporary Art, University of São Paulo, Brazil (Original)

One of the 20 th century’s most famous works of art is this concept from Italian Futurist Umberto Boccioni. Art historian Ian Chilvers tells us Boccioni in this piece depicts a human-like form in dynamic motion.

Indeed, Futurists like Filippo Marinetti boasted that their movement left earlier art in the dust by emphasizing speed and power. For instance, as art historian Elizabeth Munro explains, Marinetti in 1910 claimed: “a fast automobile is more beautiful than the Victory of Samothrace.”

Indeed, as art historian Penny Huntsworth explains, Boccioni desired to revolutionize the famous Winged Victory of Samothrace and bring Marinetti’s words to life.

New York’s Museum of Modern Art holds a bronze copy. Finally, you may also recognize this piece from the obverse of Italy’s 20-cent euro coins.

7. Bernini’s David

Gian Lorenzo Bernini | 1623-1624 AD | Marble | Galleria Borghese, Rome

You can sum up Bernini’s interpretation of David from David and Goliath fame in one word: determination. In fact, David ’s determined face is a self-portrait of the young Bernini, himself eager to take the art world by storm. Moreover, Bernini’s contemporary biographer Baldinucci claimed that his patron Cardinal Maffeo Barberini used to hold a mirror to the artist’s face as he worked on David .

As art historian Loyd Grossman points out, Bernini’s David is unique compared to many depictions of this Old Testament hero. One clear difference is that unlike many portraits of David , Bernini shows him in the climactic buildup to the triumph over Goliath.

Not ready to book a tour? Check out our Vatican Guide for more info.

6. Donatello’s David

Donatello | c. 1440 AD | Bronze | Bargello Museum, Florence

We’ve previously seen David of biblical story David and Goliath fame from Bernini. However, Donatello’s David is of special note. Why?

For starters, art historian Ian Chilvers says this was the first freestanding male nude produced in Europe for over one thousand years. In other words, Donatello became quite the mold-breaker and trendsetter. In the Middle Ages, Europeans considered the human body dirty, shameful, and best covered up. On the other hand, Renaissance artists challenged this conception. For instance, art historian Elizabeth Munro notes Donatello here drives home David ’s nudity by fitting him with a hat and boots.

Moreover, David ’s pose is reflective of someone who knows they are kind of a big deal.

5. Michelangelo’s David

Michelangelo | 1501-1504 AD | Marble | Accademia Gallery, Florence

So, you might be saying, “What, another David ?” However, this is not your average Dave. In fact, Michelangelo’s David is the ultimate creative expression of Renaissance ideals.

Unlike Donatello’s David , Michelangelo’s David has muscles that make him look like a guy who lifts. Michelangelo made sure David oozes confidence and power. As art historian Dana Arnold notes, no work heralded the rise of Renaissance culture and thought quite like Michelangelo’s David.

What is more, Michelangelo was only 26 when Florentine leaders commissioned him to sculpt a patriotic symbol of their republic. Michelangelo, as art historian Elizabeth Munro argues, not only did that: he let everyone know the Dark Ages definitely were a thing of the past.

Not ready to book a tour? Check out our article on the best Florence tours to take and why .

4. Venus of Willendorf

Unknown | c. 25,000 BC | Limestone, Red Ochre Pigment | Natural History Museum, Vienna

No bigger than your smartphone, Venus of Willendorf dates from long before the end of the Ice Age. In fact, art historian Elizabeth Munro tells us the piece dates from the Neolithic era.

Its name derives from Willendorf, Austria, the 1908 site of excavation. This piece forms part of what scholars have dubbed “Venus figurines.” Moreover, scholars like art historian Kathleen Kuiper believe that figurines like this represented fertility.

Furthermore, Kuiper suggests that because of its small size (just 4 and 3/8 inches) and the figurine’s limestone material (not found in Willendorf) that it was made elsewhere. Ultimately though, Kuiper says we know very little beyond measurements and where it was found.

3. Venus de Milo

Unknown | c. 100 BC | Marble | Louvre Museum, Paris

One of the most instantly recognizable works on our list. Venus or Aphrodite in this case is the product of different Classical Greek and Hellenistic styles.

A humble farmer discovered Venus on the Greek island of Milos (Melos) in 1820. Art historian Ian Chilvers notes that it made its way to the Louvre the following year. Chilvers says it became an instant hit. For example, Europeans were just starting to get into neoclassical styles.

Moreover, what sets this Venus apart is that it is a rare Greek original and not a Roman copy. Furthermore, much is made of what her missing arms would depict. For example, some scholars including Ian Chilvers hypothesize she originally held an apple-like Venus Victrix (Venus Victorious).

Not ready to book a tour? Find out if a Louvre Museums tour is worth it .

2. Pietà

Michelangelo| 1498-1499 AD | Marble | St. Peter’s Basilica, Vatican City

The sculpture that made Michelangelo famous. In fact, Michelangelo was only in his early twenties when his powerful Pietà debuted to the public for the Holy Year 1500. Art historian Ian Chilvers tells us the term Pietà refers to the depiction of the Virgin Mary holding the body of the dead Christ on her lap. Furthermore, Chilvers says that while the concept originated in 13 th century Germany, Michelangelo’s sculpture in St. Peter’s is the most famous example.

Moreover, art historian Alta Macadam points out Michelangelo sculpted this moving piece for French ambassador Cardinal Jean de Bilheres de Lagrulas. Furthermore, one fun fact is that this is the only sculpture Michelangelo inscribed with his name (on the ribbon falling from the Virgin’s shoulder).

Furthermore, Michelangelo returned to the subject in other works located in Florence and Milan. Sadly, as historian RJB Bosworth reminds us, it has been behind bulletproof glass since a deranged Hungarian tourist attacked the sculpture with a hammer in 1972.

Not ready to book a tour? Check out our guide to St. Peter’s Basilica for more info.

1. Winged Victory of Samothrace

Unknown | C. 190 BC | Marble | Louvre Museum, Paris

Truly the grandest sculpture on display in the grandest of venues. Originally, the statue crowned the Greek island of Samothrace’s Sanctuary of the Great Gods. As art historian Nigel McGilchrist explains, this dramatic seaside sanctuary served as the heart of a mysterious cult of the Great Mother.

Scholars believe the piece originally stood above a rocky pool. Furthermore, art historian Ian Chilvers says presumably it commemorated a naval victory. If so, this sculpture captures the moment where Nike, the Greek goddess of victory touches down on the Greek flagship to congratulate the victorious fleet. Moreover, scholars also debate about her missing arms. Ian Chilvers believes it is likely that Nike’s right arm would be raised in a victory sign familiar to any sports fan of today.

While the ancient sanctuary may be mysterious, there’s no mystery why this is truly a masterpiece of Classical Greek statuary. For starters, thanks to art like this, we have so many examples of Greek art preserved through the Romans and beyond.